A review of Mathieu Cardin’s exhibition, presented at the artist center L’Œil de poisson in Quebec City at the end of 202, published in the n° 266 (Spring 2022) of Vie des arts.

Mathieu Cardin

More Data, More Noise (Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc)

L’Œil de Poisson (Québec), November 19 December 2021

In his recent exhibition at L’Œil de Poisson, Mathieu Cardin examines the hypnotic illusionism of the screen, which is so omnipresent in contemporary society that it seems transparent.

As we enter the large gallery of the Quebec City artist-run center, we are confronted with its distinctive bluish light and the uninterrupted fading animation of the images it presents to us. We find screens of various dimensions fixed to the wall, presented on pedestals or staircase structures. The installation invites us in a way to make the tour. Objects in themselves, we find in the center of the gallery a screen next to an imitation of an ancient column, at the top of which is a rock of a lightness that we guess is deceptive. The liquid crystal display is much less visually complex than its predecessors, and is displayed as a flat surface similar to a painting. The whole exhibition attests however that the technical device which conditions the regime of visibility, although hidden, does not remain less powerful.

As soon as we stroll through the space, we are indeed confronted with the other side of the set. The layout of the gallery creates two distinct spaces. The first, larger, is presented as a technical phantasmagoria. One discovers a showcase of visual effects and illusions created by tinkering and small arrangements, both technical and material, when entering the next space, which is laid out like a backstage. Here we understand that the images seen earlier proceed from combinations of objects and materials animated by changes in lighting, the spilling of a steaming liquid or the movement of their support, captured by surveillance cameras. In this context, the screens broadcast in real time the changing states of objects, materials and devices integrated into a device imagined by Cardin, eliminating the delay between the capture and the diffusion of images, observation and exhibition.

Of fake appearance, the matter and the very manufacture of the elements put in scene bend upstream of this regime of visibility, so much they are thought for their seizure by the camera. In front of us, the images thus change instantaneously in an uninterrupted flow. This phenomenon constitutes moreover the principal characteristic of the screens on which are anchored today an increasingly important part of our visual and material culture, according to Divina Frau-Meigs, professor in information sciences (1).

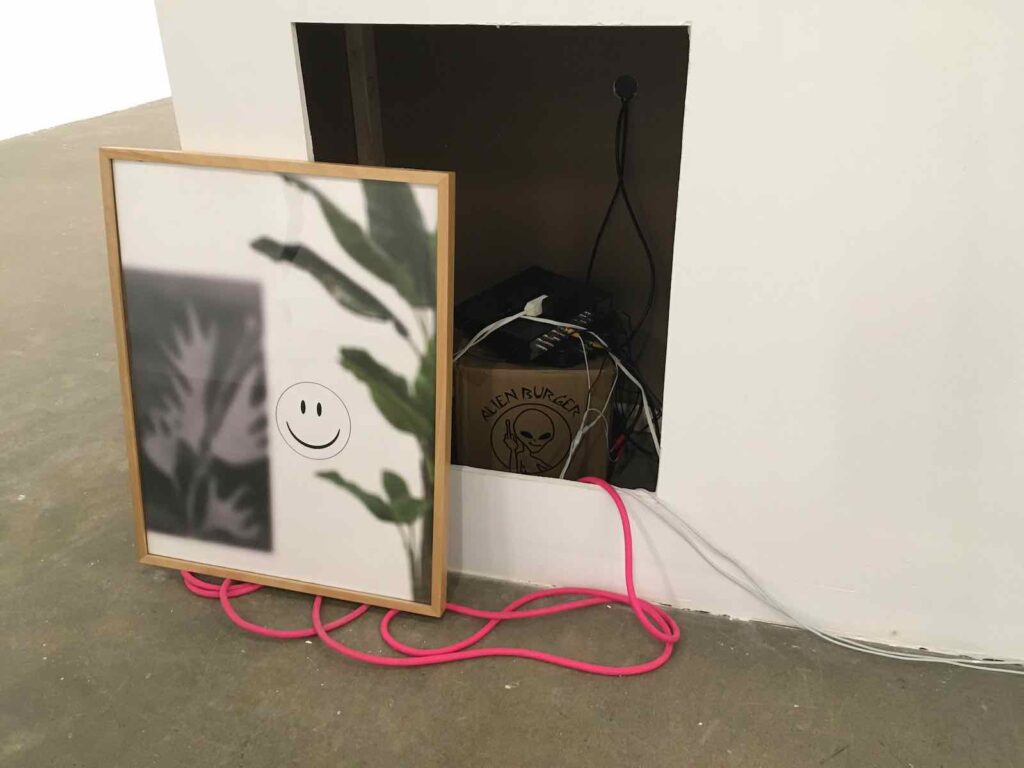

Because of their small size, the screens put forward by Cardin refer to the domestic apprehension that we have of them, different from our experience of movie theaters. They concretize the level of intimacy maintained with us, as subjects, via their device, and the proximity that has allowed them to penetrate most homes today. Without appearing to be so at first sight, this intimate relationship is part of a logic that comes under the society of the spectacle and that of consumption, both of which are characterized by a very strong, even consubstantial, relationship between image and object. As Frau-Meigs underlines it, the adaptation of the screen to the domestic sphere also concurs with the development of a liberal market (2). Hidden inside an open pedestal, an Alien Burger shipping box imagined by the artist, but of which a few restaurants later found on the Web turned out to exist, refers to this economic reality, as does the reworking of a vertical retina shape, also used as a commercial logotype in the exhibition What the Frog’s Eye Tells the Frog’s Brain that Cardin presented at Vox in early 2020.

Overall, as well as in its smallest details, Mathieu Cardin’s installation plays on this confusion between the real and its fantasized visual representation. The register of the visible modulated by the screen is based on a research of effects aiming at a greater sensation of proximity, even foaming a sensual relationship to the represented universe. It stimulates an apprehension engaging the body and attenuating the barriers between the subject and the object and creates a regime of perception altering the relation to the reality external to the screen. Added to this are the capacities of multiform and multisource connections of the device, engaging internal and external processes that can be simultaneously coordinated for the benefit of a tautological proliferation of images.

In this chamber of echoes reverberated ad infinitum by technology, the artist also points to the gallery, as an instance as much as an audience, as a stakeholder in this economy. We get caught up in the game of this extremely photogenic installation, which we relay on social networks, in another cascade of echo chambers.

- Divina Frau-Meigs, Penser la société de l’écran. Dispositifs et usages (Paris : Presses Sorbonne Nouvelle, coll. Les fondamentaux, 2011), p. 8. (In French)

- Divina Frau-Meigs, op. cit.

(Translated by Linguee, https://www.deepl.com/translator)