Review of the exhibition : Önenha’; Wen’wa’/ [Superimpositions]

Alexis Gros-Louis, artist (Curator: Terry Randy Awashish)

Shé:kon Gallery, Montreal, Project Space, Biennial of Contemporary Aboriginal Art (BACA), from May 7 to June 18, 2022 (Published in Vie des arts Webzine)

The 2022 edition of the Biennial of Contemporary Aboriginal Art (BACA) is part of the militant movement for the reappropriation of their lands by Aboriginal people, claims whose rallying cry, “landback”, gives its title to the event. Echoing the thematic group exhibitions, artist Alexis Gros-Louis, originally from Wendake, and curator Terry Randy Awashish, an Atikamekw from the community of Opitciwan, brought together by BACA, present an installation exploring Aboriginal expressions of belonging to the territory and the symbols of its monopolization by settlers. In a dynamic relationship to the site of the presentation, the duo highlights the history of disputed lands since the first contacts with Europeans. The exhibition unfolds in two rooms on the second floor of the Art Mûr gallery.

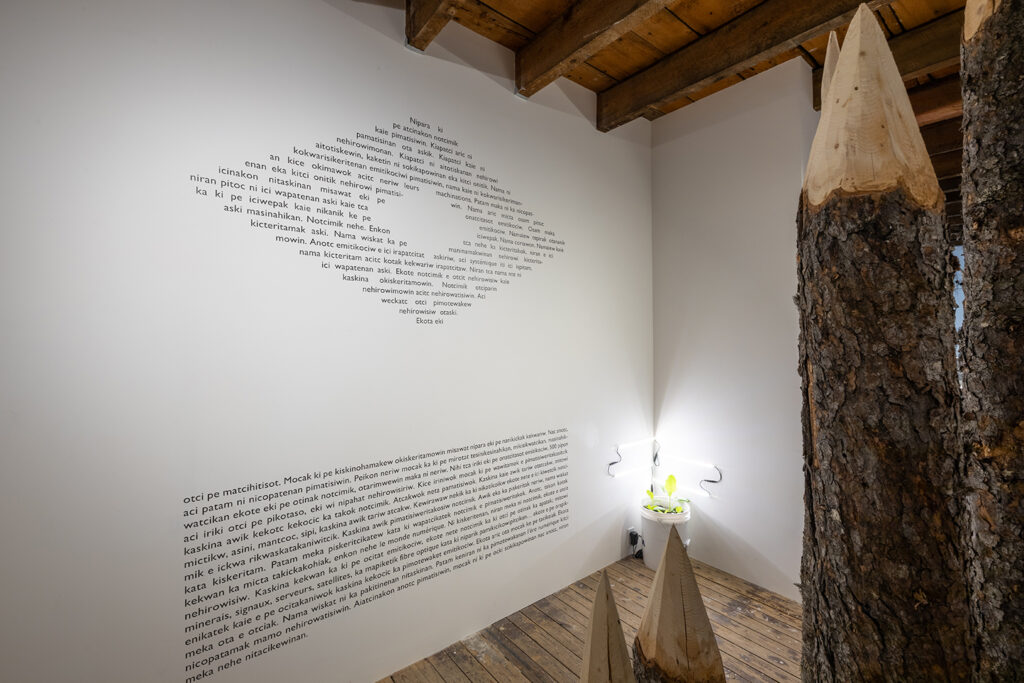

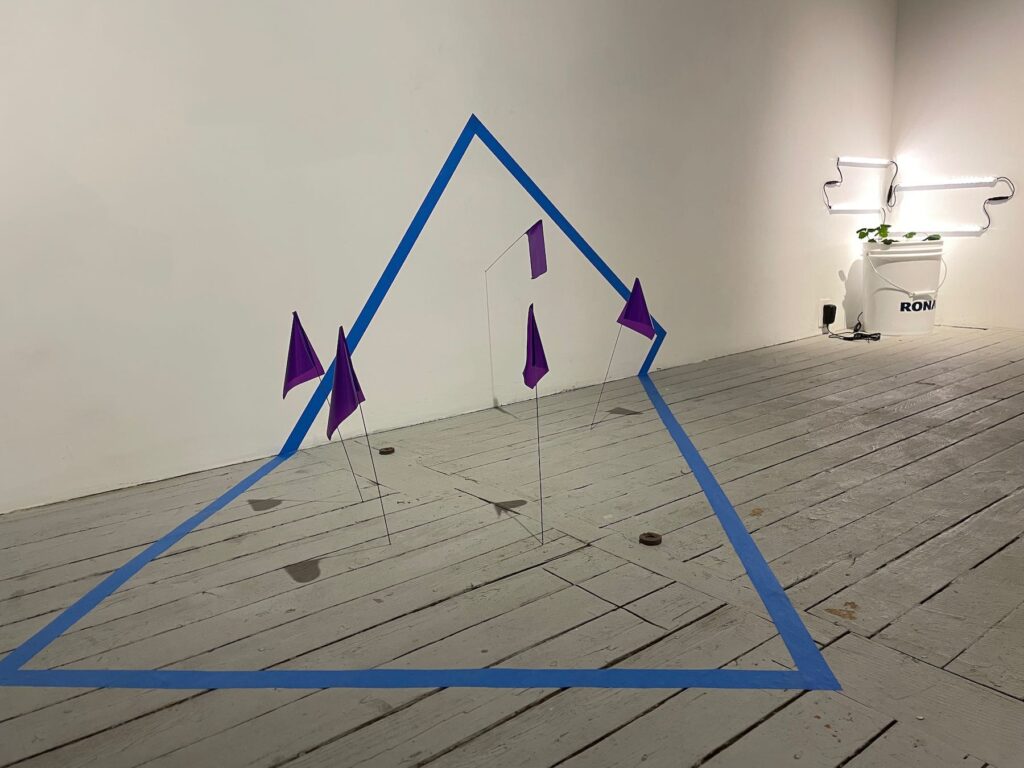

In the smallest room, near the entrance, an introductory text in the Atikamekw language breaks with the practice in Quebec of addressing a French or English-speaking audience, and deliberately affirms the nation to which Terry Randy Awashish belongs. In the center of the space, a circle of vertical wooden stakes recalls the palisades surrounding the ancient villages of the St. Lawrence and Great Lakes Iroquoians. Opposite this figure of community protection, a blue rectangle on the floor marked with a plastic flag, like those identifying the presence of pipelines or gas lines, evokes the designation on a mining claim map dissociating the subsoil from the surface and allowing the land grabbing typical of this economic sector. In a corner, under an artificial light, grows a tobacco plant, a species cultivated and prized by the Iroquoians for its spiritual virtues, attesting to their cosmogony. At first glance, these disparate elements display a whole vocabulary that expresses the customary ties of the Aboriginals to the territory and the monopolization of the latter by the colonizer. As such, they immediately situate the subject in a disputed space.

The presentation in the other room uses the same vocabulary, but enriches it with cultural references reflecting the historical evolution of these tensions. Twelve small abstract paintings, each composed of two overlapping flat tints of color, contrast a colorful interpretation of Wendat names associated with different times of the year according to ceremonial cycles with the palette of the Group of Seven, recognized as the first Canadian landscape school. These painters depicted Northern Ontario as an uninhabited wilderness, thus contributing to the construction of a national culture that ignored the precedence of the First Peoples over these lands, much like a certain American photographic tradition of Western United States landscapes to which the artists also refer. Alexis Gros-Louis reverses this dynamic and titles each of the small paintings in Wendat, in English and in French, according to the daily life intimately linked to the nature of the first inhabitants throughout the year, in accordance with the calendar of his culture from which he draws inspiration. In a gesture of reappropriation, he thus brings to the forefront what the paintings of famous Canadian painters had made invisible.

Nearby, a square meter of archaeological sculpture bears witness to a similar reinvestment of the scientific tools and methods used to make indigenous cultures known, even to define them as belonging to the past. The layered composition of this excavation cube also evokes the geology of the territory, its evolution over a long period of time well beyond human history. The use of manufactured building materials, such as concrete, wood, polystyrene foam and artificial grass, also highlights the system of extraction, production and consumption that prevails today in the exploitation of resources. This economic system, from which many indigenous communities are excluded, does not ensure them equitable access to the same building materials. A similar critical intent animates the presentation of pottery shards in designated areas on the gallery floor marked by plastic flags. Here, the grouping of these and their arrangements are inspired by the Mnjikaning fishing weirs, the largest and best preserved in North America, in use since about 3300 BC and used for centuries prior to 1650 by the Wendat, now designated a historic site in Ontario. I also saw the angled branches used by the Innu to communicate in the forest, during travel related to their traditional way of life.

In this installation, artist Alexis Gros-Louis and curator Terry Randy Awashish reappropriate a vocabulary specific to their reciprocal nations, both of which are representative of the two major groups of First Nations in Quebec, the Iroquoians and the Algonquians. By redefining them from within, they succeed in denouncing the colonial relationships that have weighed on them, while at the same time developing a personal contemporary plastic language.

(Translated by Linguee DeepL translator)