My father was a geologist and my childhood was steeped in the scientific vocabulary specific to his field. To me, words like igneous, metamorphic and sedimentary rock embody the hard kernel of my father, his fascination with apparently inert matter and his singular awareness of long duration.

Still immersed in this world, I am now looking at the works of Diane Borsato and Mat Chivers, two artists who highlight the complex relationships we maintain, collectively and individually, with mineral matter, which is still a fairly common raw material in art. By virtue of this connection, their respective approaches critique the mining activities that underpin our current economic situation.

In Québec and, indeed, throughout Canada, the mining sector maintains close relations with the world of art, particularly because art patrons who have derived their fortunes from mining have helped to fund the missions of many art institutions. Pierre Lassonde is the most well-known of these patrons in Québec due to his contribution to the pavilion of the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec that bears his name. Such philanthropic relationships support the cultural community at various levels and complicate the interdependent relationships that exist between the mining industry and culture. For example, the presentation of the collections of the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), which the Canadian artist Diane Borsato comments on in a video analyzed further on, is sponsored by Vale Inco and Barrick Gold, both mining companies. The latter, which has been investing in the educational activities of the ROM for several decades, took legal action, however, against Écosociété, the publisher of philosopher Alain Deneault’s Noir Canada, which denounced the mining activities of Canadian companies in Africa. The dispute resulted in an amicable settlement that halted the publication of the work after it came out.

Running counter to the most commonly held views, which construe mineral matter as wealth to be exploited in the form of ore or precious stones, Diane Borsato has made herself a voice for other perspectives. In the video Gems and Minerals (2018), four performers take the viewer on a one-of-a-kind tour of the ROM’s rich collections, which are among the largest in the world. In connection with the specimens on display, their expressive performances in American sign language, with subtitles, describe various issues ranging from the economic to the cultural: the craving for minerals expressed by states throughout different epochs; the use of minerals in pigment production and their symbolic value; the controversial aspects of mining operations, particularly violence and oppression; environmental contamination; tax evasion and the corruption and fraud associated with this sector of activity. The performers also do dance movements that mime anecdotes surrounding the fetishes and strange fascination called forth by certain precious or semi-precious stones. Originally viewed as inert, mineral matter now appears as intrinsically linked to human life through beliefs, history and culture, as well as through its decisive and often devastating impact on societies.

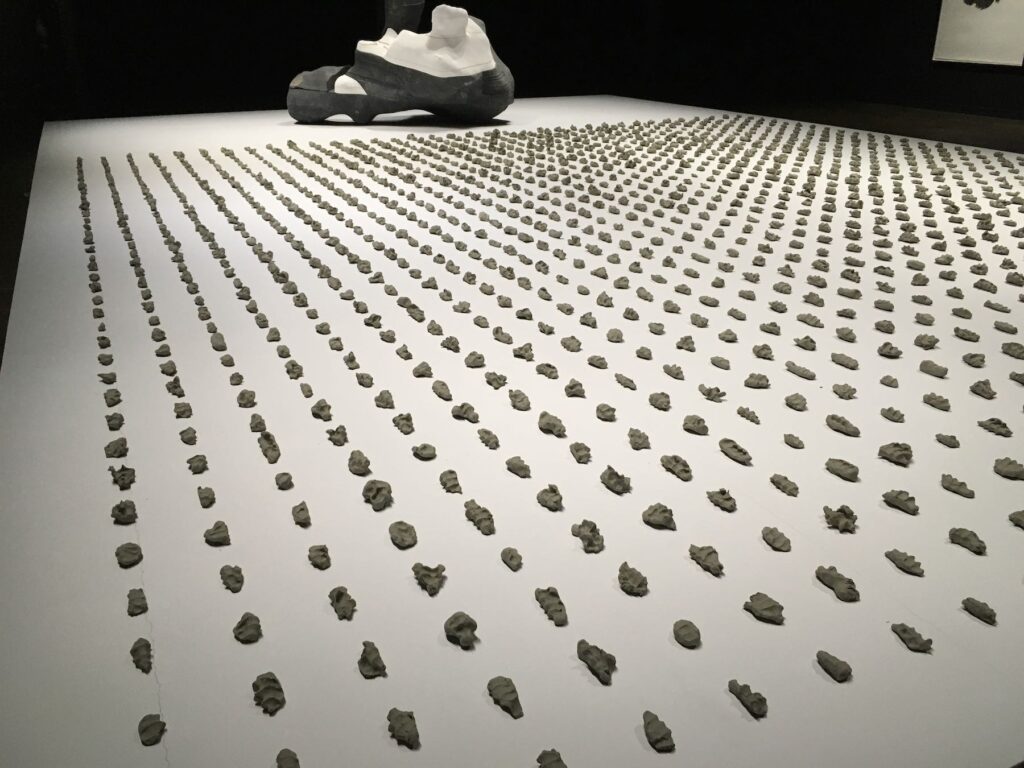

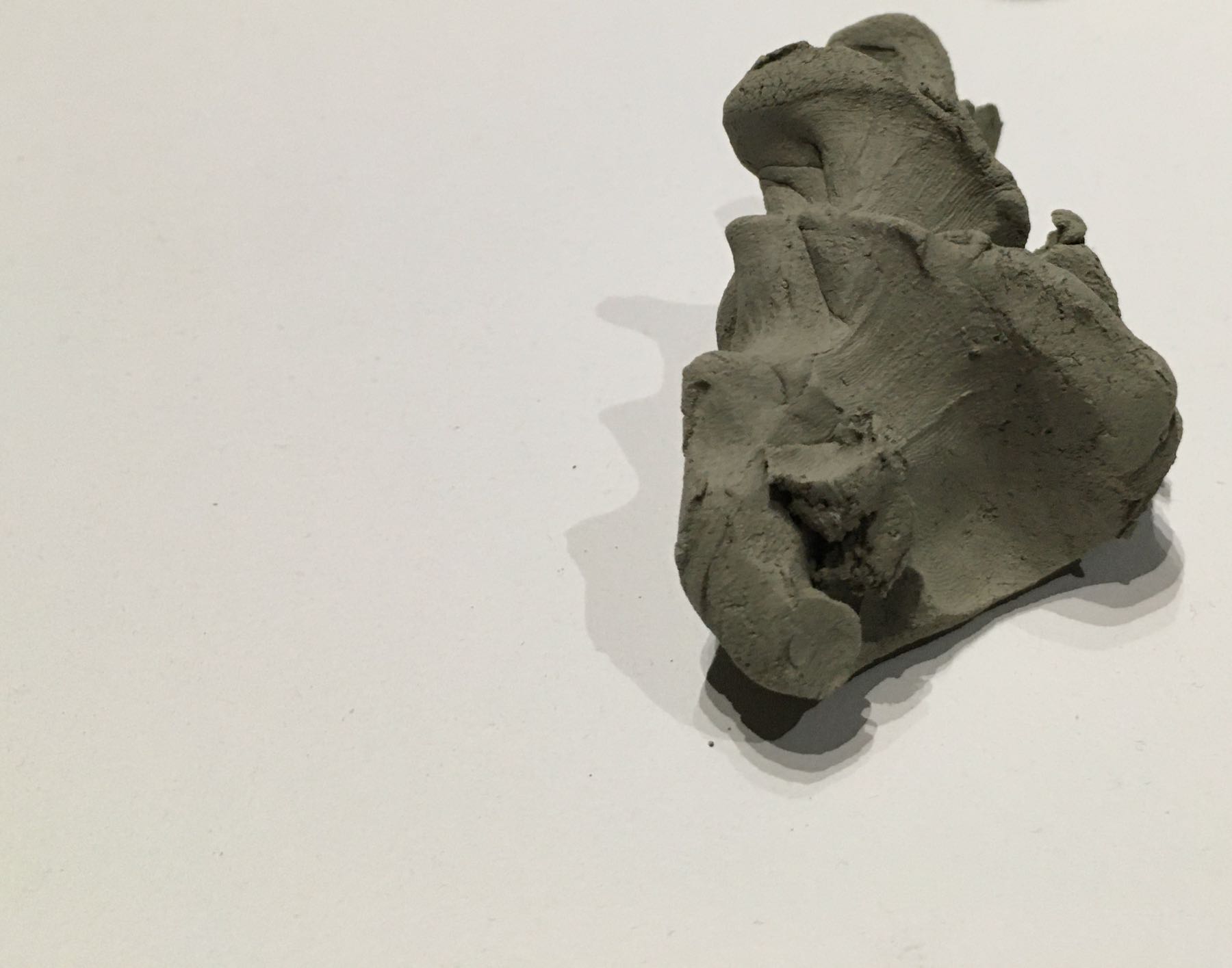

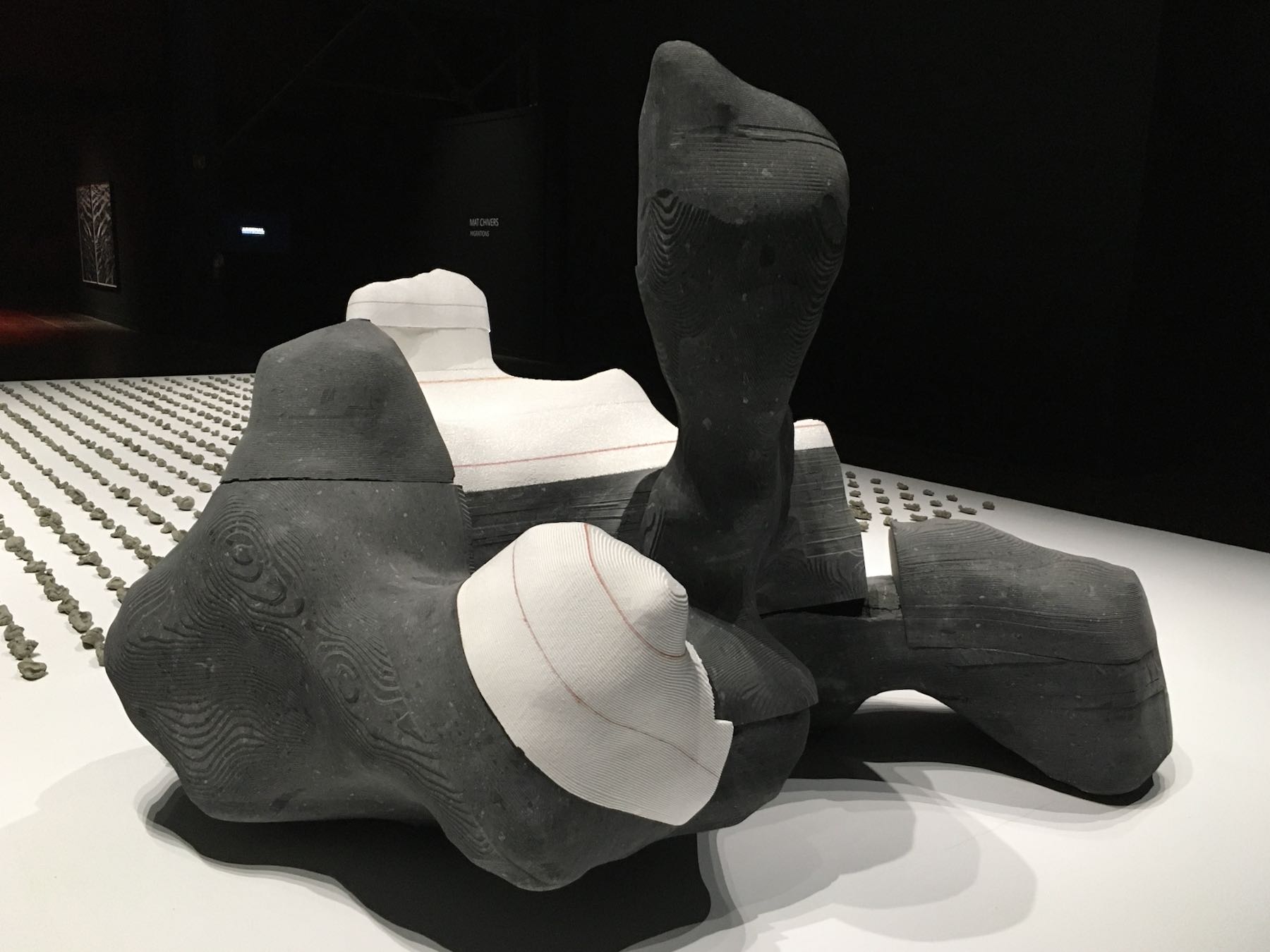

The British artist Mat Chivers is also interested in historical geology and in the ways that minerals have been used over time. His installation Migration (2018) drew up an archeological profile of humans’ interactions with terrestrial matter, going back to the direct handling of it in the form of clay and taking in its mechanical extraction in rock form. Arrayed across an imposing white platform were 1480 sculptures made by an equal number of people, each of whom had left an imprint of a hand in soft clay collected in the vicinity of Mont Saint-Hilaire. This sedimentary residue goes back over 10 000 years to a time when the Champlain Sea covered the Saint Lawrence River Valley. One end of the exhibition platform was dominated by an enlarged specimen of a fistful of earth; generated using AI, it was designed specifically for the project and programmed to respond to the information relating to each smaller specimen, thereby creating a new form using its own learning capacity. Part of this sculpture was made from a piece of impactite from Cap-aux-Oies. This metamorphic rock, produced by the fall of a meteorite some 450 000 000 years ago, was mined using mechanical means and shaped using digital technology. The work as a whole alludes to 200 000 years of evolution ranging from humans’ first contact with primary materials to the inception of technologies that could soon outstrip them in terms of intelligence.

Here, within a fluid ensemble, Mat Chivers links historic geology, the means used to collect and transform mineral matter and technical evolution as it relates to the history of civilizations. Human life and primary matter as well as their mutual interactions are shown as actors in the stories that have been passed down to us. In this regard, Mat Chivers and Diane Borsato have arrived at the same conclusion as the writer and economist Felwine Sarr: “The world we have built and continue to create is the result of numerous relationships, ranging from the inter-human and the inter-statial, with matter, living things and the cosmos.”

On a different scale – that of the charcoal drawings in the series Where Do I End and You Begin (2018, in progress) – Chivers applies himself to a creative discipline that supports this perspective on interdependence. The drawings, in diptych form, show left and right profiles, facing off, of three species of migratory birds that nest in Quebec, along with depictions of the two hemispheres of the human brain. Chivers draws first with his right hand (he is right-handed) and then copies the result with his left hand. To achieve this ambidextrous feat, he imposes a strict discipline on himself, one that activates and develops the required areas of his brain, recognizing in the process his own plasticity and its nature as a form of matter. This considered action of Chivers’ attests, on an intimate scale, that processes and materials we employ on a daily basis, and that change over time, have an impact on the body and the mind. The reference to the migration of birds alludes, in turn, to the planetary mobility between the northern and southern hemispheres, which is echoed by the exchanges between the left and right lobes of the brain brought about by the artist’s ambidextrous performance. Chivers thereby lends his action a wholistic significance and makes it a microcosm of the relationships between humans and the planet that nurtures them.

Diane Borsato uses mineral matter to weave a network of entirely novel relationships. Over the past ten years, she and Amish Morrell have been leading a project rooted in original observation activities carried out by a group she has dubbed the Outdoor School. In its wake she organized, during a residency at the Banff Arts Centre, an eclectic geological tour to study the site’s glacial erratic boulders, rocks sold as souvenirs in specialized shops and the countertop stone employed in interior decoration and acquired from suppliers in the region. Modelled on the progress of the amateur naturalists’ activities, Geology Tour in the Rock Shops (2018) was a sense-based exercise that encouraged participants from different backgrounds to speak to one another about their reciprocal sensual and motional experiences. The subtext of the activity painted a picture of the complex relationships that humans have on a daily basis with minerals, using situations ranging from the purchase of souvenirs to the consumption of primary materials, both of which emerge from diverse market dynamics.

While matter in art is often viewed as a raw material subject to the artist’s desire or creative skill, the approaches of Mat Chivers and Diane Borsato draw from it a complexity that cannot be ignored; and they invite us to take responsibility for our relationship of mutual dependence with it. Given the emotional charge that stone has always had within the context of my family, this form of questioning resonates quite strongly for me.